The Failure of the Spinning Jenny

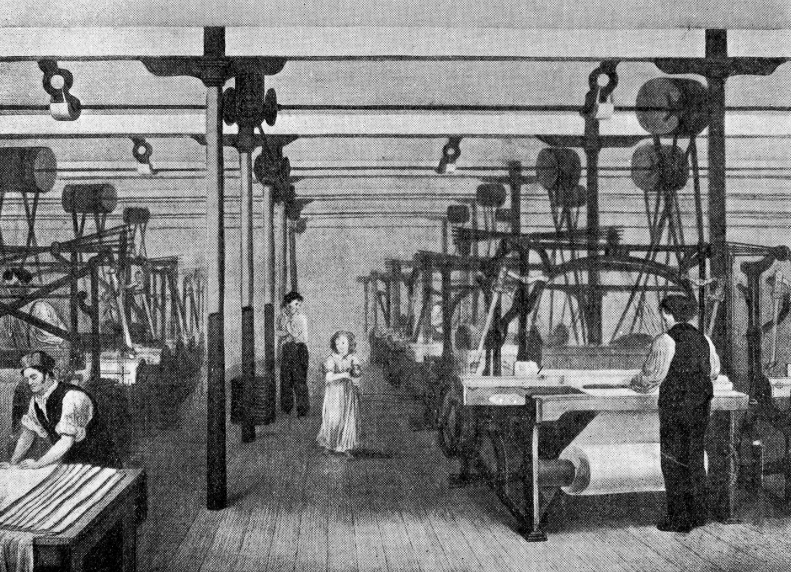

Recently, I noticed that the Spinning Jenny, which revolutionized textile manufacturing, was first invented in 1764 (and patented in 1770) in England. This got me thinking...when was this type of machine first established in the United States?

It turns out, the first attempt to do so was in 1785 by Gilles de Lavallee. Although Lavallee’s mission was ultimately unsuccessful, his adventure sheds an interesting light on the young nation’s troubles under the Articles of Confederation.

Gilles de Lavallee Meets the Americans

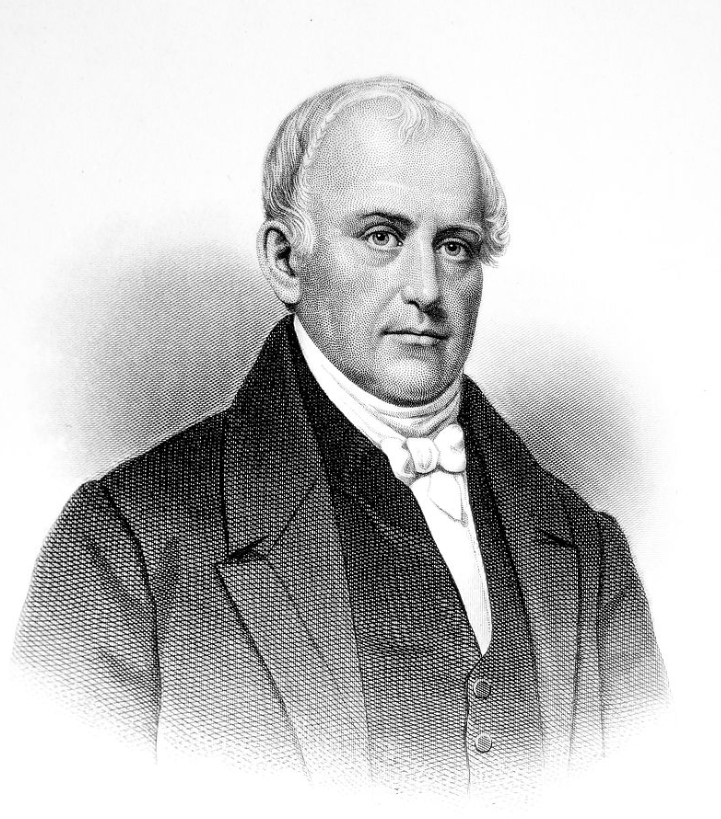

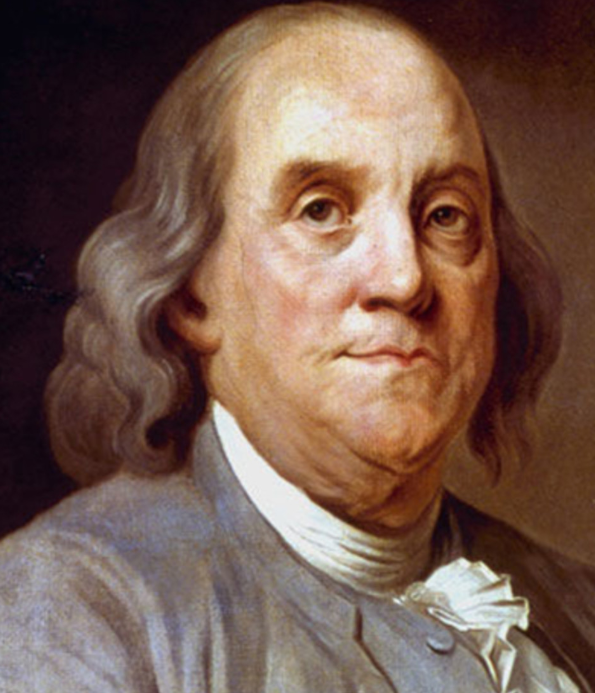

As a Frenchman, Gilles de Lavallee first became associated with the American Founding when he assisted Benjamin Franklin with the troublesome task of securing uniforms for the Continental Army.

Over the years, Lavallee discussed bringing textile manufacturing to the United States with Franklin, though the Revolutionary War was complete before an attempt was made.

When the time came, Franklin had been replaced by Thomas Jefferson. Though Jefferson gave Lavallee a personal recommendation, he denied a request for assistance from the Confederation Congress as it was not in the Ambassador’s authority to do so.

Finding Funds

Although Jefferson recommended setting up shop in the Middle or Southern Colonies (for better access to wool or cotton), Lavallee sailed for Portsmouth, NH. There, he worked with John Sullivan who had several factories of his own.

It seems that, following Jefferson’s advice, Lavallee considered this a temporary stop. He wrote a letter to George Washington asking for financial assistance to get a mill built farther south.

Washington, still in the retirement he enjoyed between winning the Revolutionary War and taking his seat as President, told Lavallee he could not help but would forward his request to Virginia Governor Edmund Randolph, which he did.

Storming Off

Randolph wrote back to Washington informing him that the State Government was about to end its session and this was not the appropriate time to introduce new business.

Unfortunately, it seems that Lavallee never received an update from Washington. Frustrated with the lack of assistance from a vigorous government, Lavallee decided to quit America and head for Spain, with whom he secured a contract to build his factory.

Lavallee wrote an angry letter to Washington, which I will quote at length here for it says a lot about the United States on the eve of the Constitutional Convention:

“...no establishment of European manufacture can succeed here—America is not suitable for the business on account of the scarsity of money—the deficiency of power in the Government—the personal interest of every member—the want of the confidence of the people in their Rulers—the fluctuation of the Legislature. You have given liberty to America—she has abused it...here, my wishes, my desires, my knowledge, my talents are superfluous, useless & even prejudicial—I depart therefore filled with respect & admiration for the great Characters, & with pity for the People.”

The timing of this letter is fascinating. Written in March of 1787, Washington was just preparing to meet with Delegates from the several States in Philadelphia for the Constitutional Convention. Much of the complaints Lavallee had regarding government would be resolved at this gathering.

A Perfect Example

Now, before we write Lavallee off as someone who just wanted some government handouts, we need to keep in mind that his complaints were the very same as many of the men who called together and attended the Constitutional Convention.

Led by Alexander Hamilton, those who would soon be known as Federalists promoted the idea of an energetic Federal Government who could actively support the growth of manufacturing in the United States.

Furthermore, it is interesting that Lavallee was supported in his efforts by Thomas Jefferson, would shortly become Hamilton’s leading opponent. Though he foresaw a nation of self-sufficient farmers, TJ clearly knew that a certain amount of growth in the textile industry was necessary to keep the United States independent of all foreign commerce if need be.

To learn about other Founders who participated in birthing the American Revolution, check out these articles:

Josiah Hornblower Makes Things Steamy

Paul Revere - More Than a Midnight Rider

John Stevens III - The Thomas Edison of the American Revolution

Want to get fun American Revolution articles straight to your inbox every morning?

Subscribe to my email list here.

You can also support this site on Patreon by clicking here.

The early Industrial Revolution coincided with the American Revolution.

‘‘A Technical and Business Revolution’ discusses the changes in the United States at this time, from the beginning through the Age of Jackson.

If you’d like a copy you can get one through the Amazon affiliate link below (you’ll support this site, but don’t worry, Amazon pays me while your price stays the same).